History & Restoration Project

North Creek Wetland

History of the Wetland

Prior to development, the lowland portion of the University of Washington Bothell/Cascadia College campus site consisted of a complex array of channels, small backwater lakes, and depressions that were part of the junction environment where North Creek flowed into “Squawk Slough” (now the Sammamish River). The hydrologic characteristics of the site were controlled by the interaction of runoff from the North Creek watershed and the natural fluctuations in water levels of Lake Washington that affected the slough.

The floodplain soils formed as a complex stratified mixture of organic deposits (mucks, peats), lake and marsh sediments, volcanic ash, and floodplain alluvium. This depositional environment varied in character from lake to floodplain with the naturally fluctuating levels of the Lake Washington watershed. When lake levels were highest, the area was a shallow part of a very large body of surface water that included contemporary Lake Sammamish and Lake Washington. Diatomaceous layers in the soil profile indicate standing water for long periods of time. However, it appears that most of the time, the site supported a complex marsh to mixed marsh-forested wetland environment. Historical floodplain sediments are mostly well-sorted medium to very fine sands. Lake and marsh environments accumulated organic soils, mostly mucks, and a variety of fine grained, mostly silt, mineral sediments. Peat deposits up to ten or more feet deep exist on northern portions of the restoration site.

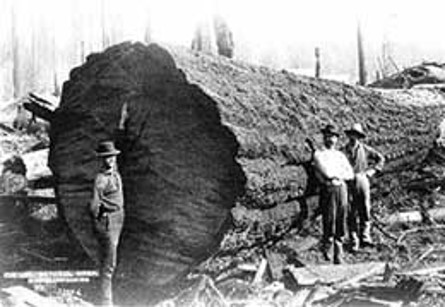

Historically, the floodplain vegetation would have been primarily forested with some scrub-shrub and emergent communities. Dominant tree species would have been western redcedar, black cottonwood, Douglas-fir, big leaf maple, and red alder. Indigenous people, including the “Willow People”, a band of the Duwamish Tribe, have called the area home since time immemorial. By 1895, the site had been logged for the first time to make way for White settlers. Maps from 1916 indicate that large portions of the North Creek channel system, including the reach that runs through the site, had been straightened and confined within artificial levees so that North Creek would serve as a flume for delivery of logs from upper portions of the watershed to Lake Washington sawmills. Following logging and since about the 1930s, the site was used for grazing or farming (most recently as the Boone/Truly Ranch). To improve site conditions for farming, extensive drainage systems (e.g., ditches and tile drains) were constructed by various owners in attempt to manage both groundwater and surface waters.

Construction of the Hiram Chittenden locks and the Montlake Cut (1913 – 1916) in Seattle connected Lake Washington to the Puget Sound, resulting in the lowering of Lake Washington by approximately 12 feet. This steepened the lower reaches of North Creek significantly, changing the surface hydrological conditions. Urbanization in the upper portions of North Creek over the last 60 to 70 years has also had significant impacts on the hydrologic characteristics of the channel and floodplain. Increases in impervious surfaces have resulted in greater runoff and an increase in peak flows.

Restoration of the Wetland

In 1993 the State of Washington purchased the 127-acre Boone/Truly Ranch site to construct a new community college and a branch campus of the University of Washington. The straightened and diked stream and its highly-modified 58-acre floodplain was vegetated with a monoculture of non-native reed canary grass and held little natural ecological value.

The campus design required that the buildings be located on the hillslope above the floodplain to minimize impacts on wetland and flooding risk. Despite the hillslope siting, the development of the campus still required the filling of approximately six acres of wetland (spring-fed hillslope wetland). Mitigation was required to account for these impacts through permitting with federal, state, and local regulatory agencies. While it would have been possible to meet the mitigation requirements on the site without restoring the entire floodplain and channel, the State of Washington made a commitment to environmental enhancement of the site that went beyond what was strictly necessary from a regulatory standpoint. With environmental sustainability as one of the stated goals of the overall campus project, the most logical and consistent approach to meeting the regulatory requirements was to restore the structure and functioning of the North Creek riverine ecosystem on the site. The planning team proposed that North Creek be reconnected to portions of its historical floodplain through creation of a new primary and secondary channel and restoration of approximately 58 acres of riverine and floodplain ecosystem.

The proposed restoration approach was recognized by the regulatory agencies as exceeding mitigation requirements for the unavoidable impacts to hillslope wetland lost due to campus construction, and conditional permits were issued in 1996. Final project approval was granted in June of 1998.

The restoration was guided by the following principles:

- Give due diligence to federal, state, and local regulatory requirements (avoid, minimize, then mitigate).

- Target no net loss of area and/or function.

- Target an on-site, in-kind approach to mitigation.

- Base the restoration design on attainable regional references.

- Target native riverine ecosystem features (i.e., plants and animals) and functions.

- Integrate the forms and functions of natural and campus landscapes.

Restoration Design

The riverine ecosystem restoration design was based upon detailed information from nearby natural reference sites, studies of the current conditions of North Creek basin hydrology, hydrologic modeling, channel constraints, and the ecological potential of the site. The design team decided that natural stream channel morphology and function would be returned by constructing a new channel system that reflected characteristics found at nearby reference sites. That is, the new stream channel system would be constructed to allow overbank flooding to occur approximately once a year. This approach would restore the functional linkage between channel and floodplain components of the North Creek ecosystem. The new main channel was designed with bed and bank features, meanders, and a variety of in-channel habitats, including pools, riffles, and large wood. A secondary channel was designed to engage at higher flow volumes.

Stream channel design targets included: (1) maximizing channel length, (2) maximizing contact time between water and wetland, (3) creating secondary high flow channels, (4) placing large wood in-channel to guide channel alignment and morphology, (5) providing for increased peak flows as a result of urbanization of the North Creek watershed, and (6) allowing lateral channel movement within design parameters.

Restoring the Floodplain

In 1997, the floodplain was scraped to a depth necessary to remove as much of the roots and rhizomes of reed canary grass as possible. Dikes were removed and drainage ditches filled. Soil was brought in and the floodplain was generally recontoured. Microtopography was added (depressions and mounds – some created with the trunks of trees that had been removed from the hillslopes to make room for campus buildings). The microtopography and floodplain woody debris provided diversity of microenvironments that allowed a variety of different plant communities to become established immediately.

Planting of over 100,000 plants took place from 1998 to 2002, proceeding from south to north. A temporary nursery was constructed on the site to propagate a portion of the required plant material and to serve as a holding and staging area for purchased plants. The site was planted with 20 general types of plant communities over 261 polygons identified on the floodplain as having distinctive environmental conditions. The majority of the site was planted as forested wetland communities, with less area in shrub- and herbaceous-dominated communities.

Management and Use of the Wetland

Initial Site Development

Restorations of natural ecosystems take a long time and this site is no exception. The native forests of the Puget Sound require hundreds of years to reach maturity. Initially after planting the site was quite sparse in plant cover but in less than 10 years the woody plants had grown to such an extent that there was a continuous canopy over most of the site. The success of native plant community development can be attributed to both design and care. The design team recognized that the disturbed, open conditions for the initial plants would require species that were adapted to and could grow rapidly in such environments. Rather than planting trees of mature floodplains, they focused heavily on early successional species such as red alder and black cottonwood. Such species have formed the cornerstone of the successful, rapid forest development. However, even with good design, many restoration projects fail to meet targets due to insufficient maintenance.

Maintenance

Over the first ten years, the two institutions have committed more than $145,000 per year to support maintenance in the wetland, primarily by hiring two full-time staff (supplemented with part-time assistants in the summer). This has resulted in an effort of 5,300 hours of labor each year toward maintenance. Summer drought caused mortality of young plants with small root systems in the early years, requiring replanting. Non-native plant species from the surrounding area found favorable places to establish in the wetland and required constant efforts in removal. Through time the tree canopy has grown up and provided shade, eliminating the high light conditions that many of our worst non-native plants require. This has reduced, but not eliminated the need for weed maintenance. As the floodplain ecosystem matures we expect further declines in the need for weed removal but the goal of a purely self-sustaining native ecosystem is probably not completely realistic as a patch of nature surrounded by an urban and suburban landscape. Other unanticipated management activities have arisen through time, such as responding to impacts that beavers have had – all the while balancing the needs of various organisms toward the goal of a diverse floodplain ecosystem surrounding a stream channel that supports a rich array of aquatic life.

Monitoring

The mitigation plans approved by the US Army Corps of Engineers, Washington State Department of Ecology, and the City of Bothell required monitoring of the site for 10 years following completion of the restoration. This compliance monitoring was designed to ensure that the restoration was progressing towards specified project targets. The information was also valuable to inform management practices that helped keep the restoration on track. Project targets were met by year 7 of compliance monitoring, and the site has been subsequently released of any further requirements under federal, state, or local permits originally associated with campus development. Research by faculty, students, and other scientists has also provided valuable information that has allowed management to adapt to ever-changing conditions.

Use of the Wetland

The wetland has become a regionally-valuable resource for education for K-12 children, college students, and professionals. Many UW Bothell and Cascadia College classes use the wetland as a living laboratory – from courses in the natural sciences to classes in art and design. Classes from other colleges and K-12 schools visit regularly and each year the site is used for professional training of wetland mitigation regulators, where they can explore what a highly successful restoration looks like.

The wetland has provided a valuable location for research by classes, individual students, faculty and other researchers. Studies have examined bats, various plants, terrestrial insects, stream invertebrates, beaver-plant interactions, water quality, stream channel development, and other topics. Long-term tracking of the development of this restored ecosystem will provide perspectives to guide future efforts in ecological restoration and the maintenance of natural areas within an increasingly urbanized region.

Looking toward the Future

Through the coming decades we expect the vegetation communities in the floodplain to mature. This process of ecological succession will include shifts in the dominance of different plant species. Some species may be eliminated altogether and new species may arise. In a natural environment species common in later succession may move in from nearby mature areas. This is less likely in our wetland, as they are surrounded by an urbanizing landscape. Thus, we will continue to manage succession through strategic in-planting of later successional species as environmental conditions warrant (e.g., western redcedar).

One of the hallmarks of this wetland is its diversity. Environmental features that often take decades to develop in floodplain ecosystems (e.g., depressions, mounds, accumulation of woody debris) were deliberately engineered into the initial landscape to “jump start” the diversity of habitats to support a diversity of plants and animals. The resulting diversity in a 58-acre patch of nature has been remarkable. As natural processes take us forward we cannot tell what will happen to that diversity, but wherever reasonable we will actively manage to maintain a healthy degree of biological diversity. In the coming years this may include a mosaic of mature floodplain biological communities, considerably different from the present-day early communities.

We expect the stream channel of North Creek to remain a dynamic feature on the landscape, slowly shifting its position as it carves away at some banks and deposits new material in other places. This will be managed only to the degree that we need to do so in order to protect infrastructure.