By Douglas Esser

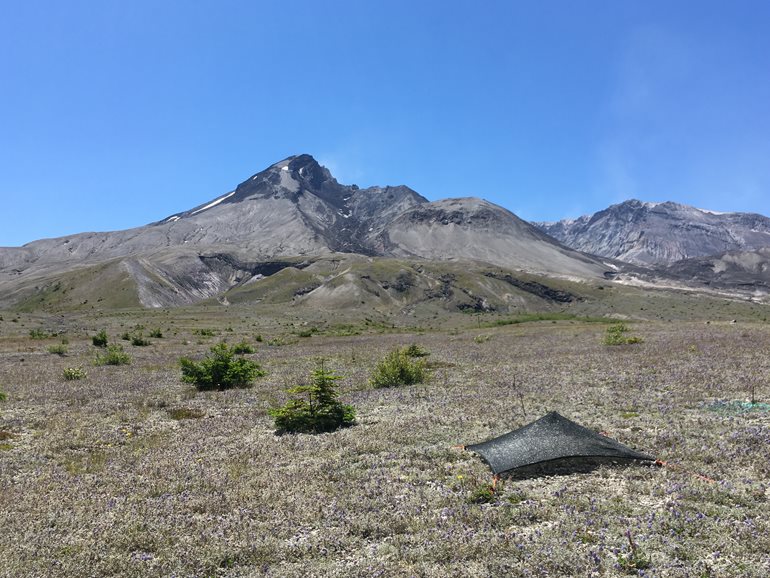

After the big 1980 eruption, Mount St. Helens looked like a moonscape.

“Nothing survived. Everything was buried. All the plants and animals were killed,” said Cynthia Chang, an assistant professor at the University of Washington Bothell who researches how plants have been recovering just a mile or two from the crater. “Our lab group focuses on the blast zone.”

It’s no longer a moonscape. Neither is it the forest that once covered the volcano. It’s somewhere in between. A few Noble fir have taken hold, looking like Christmas trees in the mossy, sub-alpine grassland.

It’s a perfect place to research plant succession — which plants come in what order and why.

Blast-zone biology

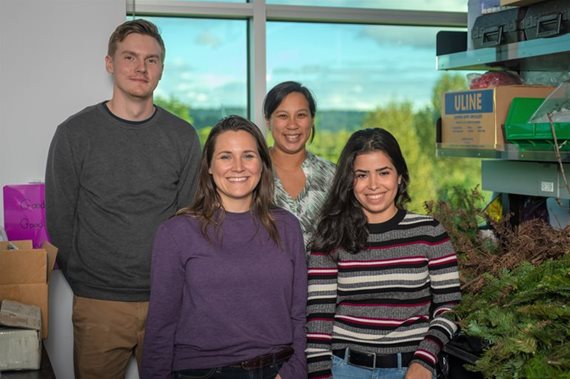

Each year, Chang includes undergraduate students in her ongoing research.

Last summer, she launched her latest seasonal field work with Alex Wachter, Katey Queen and Isabel Rodriguez, some of her biology students from the School of Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics. Continuing mostly on their own, they made more than a dozen trips, camping three to four days at a time in an area that is restricted to researchers with a U.S. Forest Service permit.

To work at an elevation of over 4,000 feet, the researchers had to wait for the snow to melt for their first visit in June. They backpacked about five miles from the Johnston Ridge Observatory to the camp and another two miles to the research plots. Later, after the Forest Service opened an unpaved road to Windy Ridge, it was only a two-mile hike.

Wachter, Queen and Rodriguez tied down shade cloths, collected branches, surveyed species coverage on square-meter plots and recorded data. Sometimes they were alone. Sometimes other researchers on other projects made a camp of 30 to 40 people. They saw elk close-up. They also saw mountain goats and their kids, chipmunks, gophers and grouse. At night they could build a campfire and eat s’mores.

Their most important task is to build on data compiled by other researchers, notably Roger del Moral, a UW biology professor who studied the blast zone for 30 years. Chang was involved in the research as a post-doc at the UW in Seattle and kept at it when she joined the UW Bothell faculty in 2014.

Long-term data

“We have continued to sample some of the same plots,” said Chang. “We’ve also started new experiments trying to understand the new community changes that are projected to happen.

“We know the plant community develops in a successional way,” she said. Observers note a progression from grasses to flowers and bushes to trees, such as the Noble fir, which is native to the Cascades.

“The firs are going to have a huge influence on the rest of the plant community as they get bigger and become more abundant,” she said.

The field research is conducted in about 40 plots. Each one has a Noble fir and sections where nitrogen or carbon are added. Another section is covered with a shade cloth. Another is left untouched, as the control.

Understanding the mechanism that drives plant succession can be valuable to people working on any ecological restoration, Chang said.

It’s also current research she brings to her biology and plant ecology courses back on campus.

Opportunities for undergrads

Chang’s plant ecology course was one of the first Queen took in the spring of 2019 after she transferred from Edmonds Community College. She loved the classroom in the Sarah Simonds Green Conservatory and read every page of the textbook. She jumped at the chance to conduct research at the volcano in southwest Washington.

“It’s outdoors, it involves hiking and sunshine, and I’ve always loved Mount St. Helens,” said Queen, who has a jar of the volcano’s ash that fell on her grandmother’s garden in Coeur d’ Alene, Idaho.

“Having that opportunity as an undergrad — before I start making decisions about grad school or a career — opened up what it is really like,” said Queen. Now a junior in Biology, she says she who would like to work in career related to ecology or conservation.

Rodriguez, a senior majoring in Biology, grew up in Nicaragua. She’s interested in how the research can be applied in the tropical country, which has been impacted by the exploitation of natural resources.

“It definitely gave me a view of what this type of work looks like,” said Rodriguez, who is considering graduate school and wants to work in biology or ecology.

Wachter, an Earth Systems Science senior, received a Mary Gates scholarship to support his work with Chang in the summer of 2018. He was the team leader for the 2019 field work.

Growing up in Monroe, Washington, Wachter saw deforestation from logging, which is one reason he’s interested in plant succession. Also considering grad school, he’d like to work for the Forest Service or Park Service.

Not your typical biology lab

It’s unusual for undergraduate students to conduct research at Mount St. Helens.

“I would say this team has been doing master’s level work,” Chang said. “They’re very independent. They are collecting data that will be published.”

It’s not what most people imagine as college biology, said Queen, who will be team leader for next summer’s research.

“When you come to school you think biology is indoors and lab-focused,” she said. “I think it’s amazing we had this opportunity to be outside and then come back and do data analytics on top of it.”