By Douglas Esser

Some once-cool cans of soda are warming up to demonstrate how recycled cans could help heat a tiny house for the homeless.

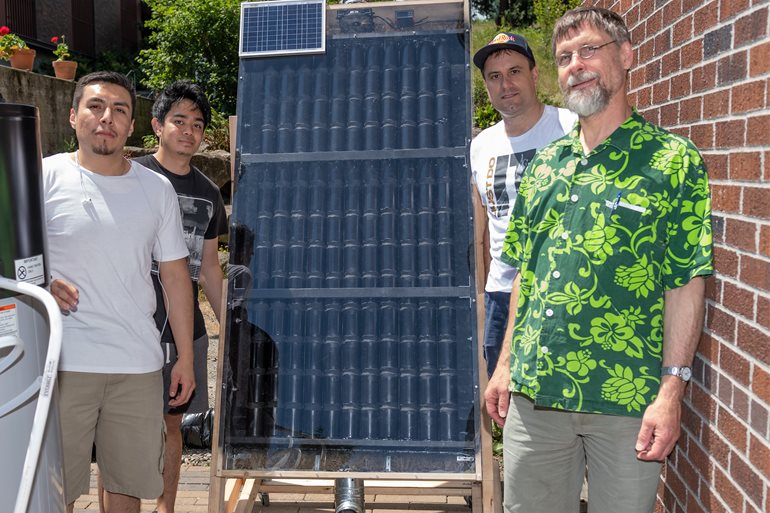

Four University of Washington Bothell Mechanical Engineering students built an inexpensive soda-can solar heater as part of an innovative capstone project. First, they took recycled aluminum cans, expanded the hole in the top, opened the bottom and then stuck them on top of each other to form long tubes. After spray-painting the tubes black to absorb heat, the students placed them in a 3-foot by 6-foot wooden box covered with a Plexiglas top.

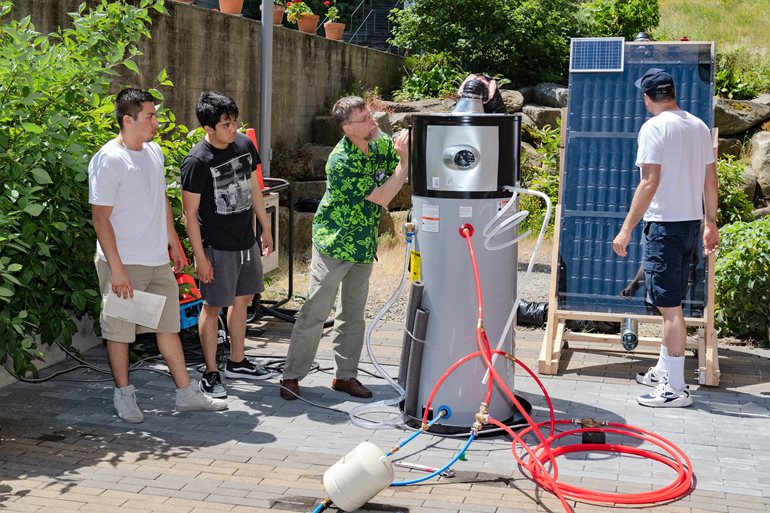

In a test on a sunny day in June outside Discovery Hall, the air came into the heater at 77 degrees and blew out at 105. That temperature gain alone might heat a tiny home when the sun shines, but alas, there aren’t enough of those days in Seattle to use the soda-can solar heater by itself. The innovation came in how the students engineered it to work with a heat-pump water tank.

Community partnerships

The four who graduated this June — Justo De Asis, David Bill, Ryandi Lim and Jorge Sanchez-Perez — worked together under the guidance of Imen Elloumi-Hannachi, a visiting lecturer in the School of Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics (STEM). She connected them with two sponsors in Seattle aiming to provide housing for the homeless. The BLOCK Project is an initiative to locate one 125-square-foot home within each residential block in the city. The other nonprofit, ecoThrive, plans to build a 20-unit tiny home village.

The students provided the problem-solving and engineering skills, while Elloumi-Hannachi guided them with project planning, management and acting as their liaison with their clients.

“We’re looking for really low operating costs,” said Lars Henrikson of ecoThrive, the industry adviser for the capstone. “We want it to be low energy use and designed for how people should be living in the future as we get into a carbon constrained world. We want affordable housing for everyone.”

The most technical part of the soda-can heater is a small, solar powered panel that provides electricity for a fan and thermostat. Air flows from the bottom of the heater, through the tubes and out the top. As with a closed car on a sunny day, the heat inside can build up fast.

Like a hot car

The students took advantage of that. They came up with the idea of using the solar heater in combination with a commercially available heat-pump water heater, Henrikson said. It looks like a typical water tank, only with a heat pump on top, which reduces electricity use. Drawing air from the solar heater increases the heat pump’s efficiency.

“Just raise the temperature of the air going into the heat pump, and the heat pump isn’t going to have to work as hard,” said Henrikson, who also has experience managing conservation programs for Seattle City Light.

Heating efficiency

In addition to providing hot water for a tiny house, water from the tank would run through tubing in a floor for radiant heating. The house would then not need electric baseboard heating.

“I wanted to see if we could take a heat-pump water heater — which uses half the energy of a regular water heater — and see how that could also be the heating system for a tiny house,” Henrikson said. “So, use a heat pump and get twice as much heat out of the same amount of electricity.”

Using an industry method of estimating heating needs, it would take a 5,000 British thermal unit (Btu) source to heat a 125-square-foot room. The students calculated that their solar heater added 2,246 Btu to the system, or nearly half of the heating needed for a tiny house that size.

HVAC experience

Perez, De Asis and Bill tested the project, as Lim was away, and presented at the spring STEM Capstone Colloquium in the Activities & Recreation Center on campus.

The three said the project was more complicated than they first thought. It wasn’t just fitting components together. There were a lot of trial and error iterations. There also was more plumbing and ventilation labor than they anticipated, which was good experience for all three who plan to work eventually in the heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) industry.

Perez and De Asis next plan to take the Fundamentals of Engineering exam, which is required for professional engineer certification. Bill, who is retired from the Navy where he had air conditioning and refrigeration experience, is looking for an HVAC position where his ME degree will stand out.

It looks like the solar heater should work, Henrikson said. The students proved the concept. “It’s great to see there are young engineers interested in energy engineering.”