By Douglas Esser

With more human activities in the ocean — shipping, military exercises, oil exploration, wind farms — the level of underwater noise increases.

That noise has a direct impact on whales and other marine mammals, said Shima Abadi, an assistant professor in the University of Washington Bothell’s School of Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics (STEM).

“To have more activities in the ocean, we need to understand the impact of those activities on the marine environment,” Abadi said. “We need to know exactly how much noise we are adding to the ocean soundscape. Is it disturbing marine mammals and other animals in the ocean or not?”

A challenging environment

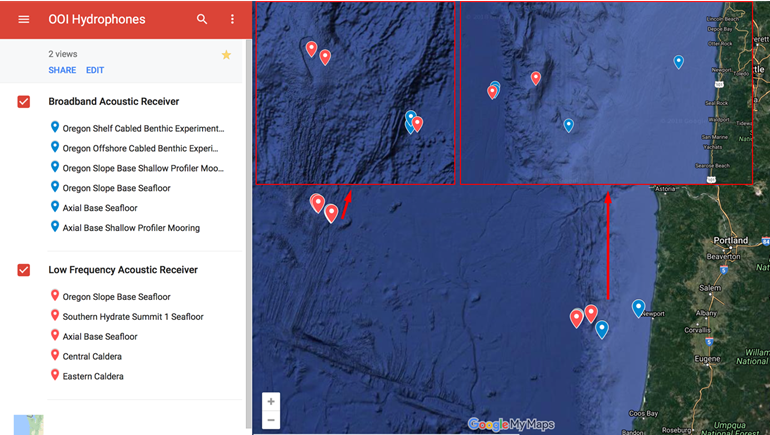

To help answer such questions, the Navy’s science arm, the Office of Naval Research (ONR), has awarded Abadi $850,000 over three years to research underwater noise off the Northwest coast. For the research titled “Data-Driven Analysis and Prediction of Ocean Ambient Noise in the Northeast Pacific Ocean Continental Slope,” Abadi will analyze acoustic data recorded by hydrophones in the Ocean Observatories Initiative (OOI).

The OOI is a global project funded by the National Science Foundation with eight arrays of sensors in different parts of the world. Two of them are off the Northwest coast.

The Coastal Endurance array monitors conditions on the continental slope in the area that includes outflows from the Columbia River. The adjoining Axial Seamount array monitors an active volcano with multiple hydrothermal vents. This is the area, about 300 miles off the Oregon coast, where the Juan de Fuca tectonic plate is sliding under the North America plate, threatening the “big one” earthquake.

The arrays connect a network of sensors, cameras and other equipment. Two hydrophones in the Endurance array and nine in the Axial Seamount array already have recorded five years of data, Abadi said.

Starting in the fall, her research will not only provide the Navy with information it can use to manage its activities, but it also will demonstrate new techniques of big data analysis — machine learning using cloud computing resources.

Can you hear me now?

This spectrogram illustrates a whale call, which shows up as the yellow at the bottom of the image. The sound was recorded by hydrophones in the Ocean Observatories Initiative (OOI) off the Northwest coast.

Some sounds can travel huge distances underwater. Storms off Alaska, low-frequency whale vocalizations off California, west coast ship traffic, even thermal noise from the volcanic vents contribute to the overall noise off the Northwest coast, said Abadi, who has been teaching mechanical and ocean engineering at UW Bothell since 2015.

“First, we want to identify the contribution of each component. Then, we will identify their seasonal, spectral and spatial patterns and predict future trends of the ambient noise,” said Abadi.

Her past research includes locating underwater sound sources and assessing the impact on marine mammals. Sounds of individual whales or ships hundreds of miles away may not be distinguishable, but their echoes stay in the ocean for a long time and change the ambient noise level.

Abadi’s research aims to give the Navy a way to predict how its actions affect marine mammals.

“We can learn a lot from this dataset, once we implement machine learning and cloud computing,” Abadi said. “We want to identify the pattern of each sound source category and then predict the ocean noise in the future.”

Swimming in the deep end

This new research project also has benefits for the university, students and Abadi’s teaching and outreach. One is bringing UW Bothell into the multi-university OOI group.

“It is very important to show our presence — UW Bothell is involved. Being part of this community will definitely have an impact on our students,” said Abadi, who has been promoting ocean engineering as a field of study at UW Bothell.

Abadi’s ocean engineering students have already studied OOI data to learn about oxygen “dead zones,” the ocean sound channel and the thermocline layer, where temperature changes. Two of Abadi’s students, Matthew Munson and Spencer Nelson, took part in a 2018 cruise to upgrade and maintain OOI instruments.

Training researchers in the field also is a goal of the Navy. Abadi hopes to involve UW Bothell undergraduates with a couple of doctoral and post-doc student researchers she plans to hire in the Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering at the UW in Seattle.

Citizen science

Abadi’s outreach is through her faculty affiliation with the eScience Institute at the UW in Seattle. The institute plans to engage the public in a citizen science project and is building a website that would present users a sound spectrogram — a visual representation of frequency over time. As the site will show, humpback whales, dolphins and ships all create different wavy lines.

Confirming a whale call spectrogram also creates training data for machine learning. Then algorithms could detect whale calls automatically. Click and listen. Do you hear that eerie whoo from the deep?