As technology continues to evolve, artificial intelligence is being injected into all aspects of our lives — from customer service and traffic management to social media and health care. AI chatbots capable of having human-like conversations are an increasingly popular use for the technology, offering users the ability to “talk” to bots about everything, including religion and mental health therapy.

Chatbots are even being used to simulate a digital version of a deceased person to help process grief. Using the digital footprint of the deceased — their emails, texts and social media — these griefbots, also known as AI ghosts, mimic their personality.

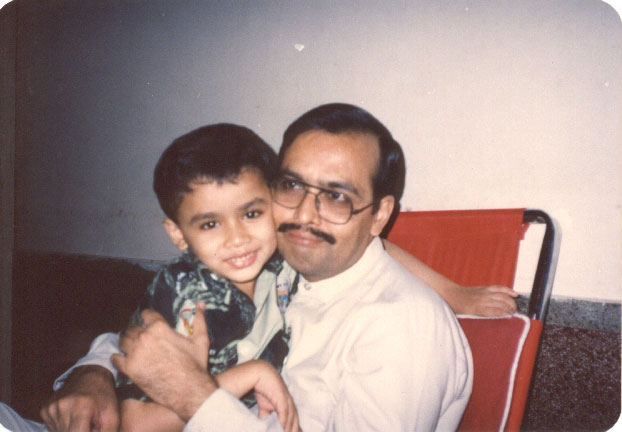

A decade ago, Dr. Muhammad Aurangzeb Ahmad set out to create such a bot after his father passed away. It wasn’t his own grief he was looking to process, however, but the sense of loss he felt for his children, who would never know their grandfather. The result: Grandpabot.

AI plugs into life and death

An affiliate assistant professor in the University of Washington Bothell’s School of STEM, Ahmad said he’s long been fascinated by AI. He grew up in Pakistan, and his father’s book agency imported books from the Western world, mainly technical books, which introduced him to the subject.

“As a kid, the idea of having machines that could perform tasks better than humans, that really stood out to me,” he said. “And the possibility that one day we may be able to create an artificial mind, I found that fascinating.”

In addition to his faculty position at UW Bothell, Ahmad is a research fellow in the Surgery Department at Harborview Medical Center. He studies machine learning and artificial intelligence, and how they can be applied in health care settings. Currently, he’s interested in the end-of-life space and looking at how AI can help determine who will survive among those with severe and life-threatening conditions.

Ahmad’s father died in 2013. When his youngest child was born two years later, he thought of his own limited time with his grandparents, who had died before he reached the age of 5. He was saddened to think that his children wouldn’t even have those few years with his father.

“One of the things that came to mind was, maybe one day I can create a simulation,” he said. Ahmad finished the first version Grandpabot in 2016 and has continued updating it ever since. “My kids have grown up with this model.”

Simulation of a loved one

To create a simulation of his father, Ahmad used letters and various writings from him. Most valuable, he said, were the audio recordings he had taken of their conversations together. Though not recorded for the purpose of the bot at the time, the conversations were often interview-like in nature and proved instrumental in capturing a digital likeness of the man. Among the recordings, he had also captured his father telling bedtime stories to Ahmad’s nieces and nephews.

When he first tried to use the model in 2016, Ahmad was overwhelmed by how real it felt.

“There were moments when I had to turn my computer off and walk away because the experience was too emotionally strong,” he said. “I had to make a deliberate decision to emotionally distance myself from the model.”

While the simulation felt true to his father’s personality, Ahmad noted that the model was specifically fashioned after the man as he knew him — but that it does not represent the whole of his life and experiences.

“When we think of a person, our idea of that person is always filtered through our lens,” he explained. “I have three siblings who are much older than me, and if you ask them about our dad when they were growing up, they’ll give very similar responses. They will say he was a typical strict South Asian dad of the 1950s. But my experience was that he was a very chilled out person — the equivalent to an American hippie dad from the ’60s.”

A decade-long experiment

In the landscape of griefbots, Ahmad said that what makes Grandpabot unique is that its purpose isn’t centered around grief, but rather providing his children an opportunity to get to know a grandfather they never met.

“It’s an unprecedented experiment in that sense,” he said. “And I would say it’s been a success. I could have told my children these stories about my father, but I think they are more likely to ask certain questions of Grandpabot that maybe they would not have asked me.”

When they were younger, he would type their questions for them, but now they can interact with the model on their own.

Because of the bot, his children are also more cognizant of the concept of death compared to their peers, he added. “It’s a subject we don’t really talk about in our culture, but because they have grown up with it, it’s not something novel or strange to them. It’s just natural.”

Over the years, he said their perceptions around death and the model have also evolved. During the pandemic, the kids got used to interacting with people in digital spaces. Because of their experiences with the bot, however, they didn’t always know if those people were real.

“When my youngest was two years old, she interacted with my sister-in-law only through smartphones during that time, and she was extremely surprised when she discovered that her aunt existed outside of the phone,” he said. “As they’ve gotten older, they now have a different understanding of Grandpabot and know that it isn’t grandpa, but it is similar and it talks like him.”

“The danger I foresee is that these companion bots can potentially be very addictive, and people may start neglecting real people and real relationships.”

Dr. Muhammad Aurangzeb Ahmad

A tool, not a replacement

Ahmad often gives talks about the Grandpabot through the Humanities Washington Speakers Bureau and finds that most people are curious and interested in learning more about the evolving capabilities of chatbots.

Griefbots are part of a much larger trend that is emerging around bots serving as stand-ins for human relationships — from childhood friendships to romantic partnerships. Despite his own experiment with the technology, Ahmad said he is cautious about the potential harm and loss of human connection that this trend could cause.

“We already have a loneliness epidemic, primarily in the West but also in Far East Asia. Many people don’t socialize and form as many friendships as they once did, and so these bots offer a way to form that connection,” he said.

“The problem is that human relationships require time and effort. People are messy and not always agreeable, but you have to work on these relationships. The danger I foresee is that these companion bots can potentially be very addictive, and people may start neglecting real people and real relationships.”

When asked whether he’s taken any steps to “archive” his own personality for future bot use for his own children or grandchildren, Ahmad said he has decided not to at this point in his life. Instead, he’s focused on creating memorable moments and bonding with his kids in the here and now.