For students who want to go into environmental sciences careers, having opportunities to get outside and get their hands dirty is an integral part of their undergraduate studies.

Even better is when learning outside the classroom leads to real-world impacts and engagement with local communities, says Dr. Amy Lambert, an associate teaching professor in the University of Washington Bothell’s School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences.

“Student engagement with places and the communities that they support is central to my teaching,” Lambert said. “Place-based learning situates students as a catalyst of change in the local community and serves as a transformative moment in students’ educational journeys. Students begin to see curriculum as lived experience as they grapple with unforeseen issues, participate in shared decision-making and engage with professionals in the community.

“For many, this is an invaluable bridge into an environmental career.”

To aid in this process, in 2021 Lambert developed a senior capstone for students in environmental majors. In the latest class, students and recent alumni focused on restoration projects ranging from soil assessment to developing pollinator habitat.

“Place-based learning situates students as a catalyst of change in the local community and serves as a transformative moment in students’ educational journeys.”

Dr. Amy Lambert, associate teaching professor, School of IAS

Assessing soil health

Richmond Beach Saltwater Park, a 42-acre site that borders the Puget Sound in Shoreline, Washington, was historically used for sand and gravel extraction in the early 20th century. Efforts to restore the park ecosystem have been underway since the early 2000s.

And Diane Brewster, an environmental scientist who consults on the park restoration, has been a strong partner of Lambert’s capstone program, often involving UW Bothell students in her work.

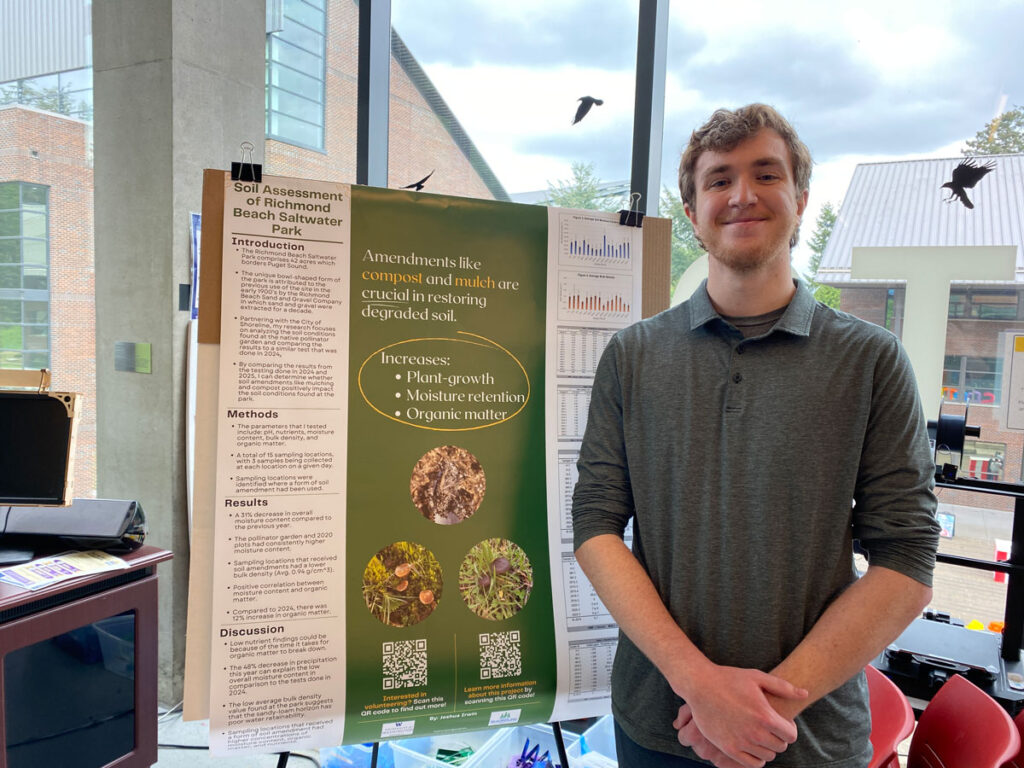

In his capstone research, “Soil Assessment of Richmond Beach Saltwater Park,” Joshua Irwin (Conservation & Restoration Science, ’25) focused on testing soil conditions and exploring their role in permaculture as a tool for restoring degraded ecosystems. He took soil samples from 15 different locations and later tested them in a lab — working with Jennifer Cabarrus, IAS environmental science lab coordinator.

“I was incredibly grateful to have the opportunity to work on this project and learn so much from not only Diane but also Professor Amy Lambert and Jennifer Cabarrus,” he said. “This was my first in-depth scientific report, and I believe it’s helped me become more passionate about restoration science as well as more confident in what I want to do in life.”

He compared data on the pH, nutrients, moisture content, bulk density and organic matter with data from the previous year and found that sampling locations that received a form of soil amendment, such as compost and mulch, had higher concentrations of moisture content, organic matter and nutrients.

“This information is critical to developing future restoration plans and ultimately helps the restoration community — staff and volunteers — focus their efforts on methods that work,” Lambert said. “It also provided managers with new insight into how permaculture might be used as a tool for restoring degraded soils.”

Developing pollinator habitat

Another organization Lambert has partnered with through her capstone course is Whale Scout, a local nonprofit organization that aims to protect Pacific Northwest whales through land-based volunteer conservation experiences.

In her project, “Restoring Pollinator Habitat through Invasive Species Removal and Experimental Seeding,” Wendy Liao (Environmental Studies ’25), focused on ecological restoration at the former Wayne Golf Course in Bothell, Washington.

When the golf course shut down in 2014, the local community fought to protect the land from development, and it was later purchased by the city in 2017. Today, the 89-acre site is the largest park in Bothell.

“This project was a perfect blend of my academic interests in environmental justice, ecological restoration and community-based conservation,” Liao said. “It gave me hands-on experience in the field, which I hope to carry forward into a career in environmental education, restoration or advocacy.”

She worked on developing pollinator habitat, wildflower planting and removing invasive species. One of the most interesting parts of Liao’s project, Lambert said, was the experimentation with lupine transplantation. A genus of plants in the legume family Fabaceae, lupine are known for their ability to convert atmospheric nitrogen into a form usable by plants. Because their roots are so sensitive to disturbance, Lambert noted that they are rarely transplanted. Successful transplantation, however, has many benefits and can improve soil health and biodiversity.

“The most rewarding part of this project was seeing how small actions can contribute to long-term ecological restoration,” Liao said. “This experience deepened my appreciation for the land and for the people working to protect it. As someone from Taiwan, being part of this local restoration project helped me build a personal connection to the place and reminded me that conservation is a shared responsibility across cultures and communities.”

Monitoring wildlife movements

For their project, Ash Putzke, a senior double majoring in Earth System Science and in Biology, supported an ongoing project with Dr. David Stokes, emeritus professor in the School of IAS, looking at wildlife in nearby Saint Edward State Park.

In a capstone called “Restoration Potential in Newly Acquired Greenspaces of Big Finn Hill Park and the city of Kirkland,” Putzke centered their investigation on two parcels of public land that had recently been secured by the Finn Hill Neighborhood Alliance as part of an ongoing initiative to connect several parks and green spaces with a continuous woodland pathway.

They used wildlife cameras deployed on upper Denny Creek near Big Finn Hill Park, monitoring an area around a stream culvert to see what wildlife species were present and whether animals used the culvert to cross Juanita Drive, a major road that crosses Denny Creek.

The cameras recorded a wide array of species, including bobcats, deer, river otters, coyotes, beavers and pileated woodpeckers. What Putzke found was that most species tended to stay on one side of the road — with the exception of “adapters” such as raccoons, which were observed using the culvert. These findings, Putzke noted, suggest that the road could be an impediment to wildlife movement and dispersal.

“I believe this property has great potential,” Putzke said in their capstone presentation. “We can improve habitat connectivity by removing barriers and expanding the vast green space of Finn Hill. I believe now is the time to be aware and invested in wildlife culvert use. As a statewide effort to replace culverts continues, we must also consider the potential to reconnect habitat and provide safe passage for wildlife in an increasingly fragmented landscape.”

The outcomes of this research, Lambert said, could inform environmental policy and restoration priorities.

A hub of activity and connection

“I am impressed with the students’ commitment to their research and how incredibly valuable these projects are to the work of community partners,” Lambert said. “All three projects contribute to the field of restoration broadly, and results of research have important implications for the conservation and restoration of each project site.”

Since launching the two-course capstone series, Lambert said she’s mentored 66 students and collaborated with 14 community partners to address environmental challenges.

“Restoration is most effective and sustainable when multiple stakeholders and community are involved,” she said. “Today, the capstone is a hub of activity that connects students, faculty, academic advisers, lab facilities and community partners in hands-on environmental projects and builds meaningful and transformative relationships to the land.”