Anida Yoeu Ali asks tough questions — about identity, otherness, discrimination — in her performance-driven art. With a presence that spans Indonesia to Australia, France to Cambodia and beyond, she has received global acclaim for her installations and exhibits.

In the process, Ali has put the University of Washington Bothell on the international arts map. “She has invigorated attention to our campus as a place of critically engaged, globally minded creative arts,” said Dr. Dan Berger, professor in the School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences.

In recognition of her contributions to UW Bothell, Ali has received the 2025 Distinguished Research, Scholarship & Creative Activities Award.

An outsized visibility

Ali arrived on campus in 2016. Along with a full teaching load as a senior-artist-in-residence, she has continued an ambitious schedule of exhibits and performances all over the world. In 2024, she installed her largest solo exhibition to date: “Anida Yoeu Ali: Hybrid Skin, Mythical Presence,” at the Seattle Asian Art Museum, the first Cambodian American to have an exhibit there. The show was on view for six months and featured two of her most prominent performance works, “The Buddhist Bug” and “The Red Chador.”

“As with most of my performance personas,” Ali said, “they are heroines and larger-than-life feminist figures: womxn who are bold, courageous and unapologetic. They are hybrid forms mixing and matching, reinventing and reimagining possibilities.”

For both The Buddhist Bug and The Red Chador, Ali uses textiles as storytelling devices, costumes and sculptural elements to extend the surface of her body. The result: an outsized visibility, both for herself and the multiple communities she represents.

Power through mythmaking

As the Buddhist Bug, Ali dons a 328-foot-long, bright orange tubular costume that reveals only her face. The orange is the color worn by Buddhist monks in her native Cambodia, from which her family fled in 1979. Look closer, and you’ll see Muslim elements in the Bug, including the headpiece that evokes a hijab — sometimes worn by women in the ethnic minority Cambodian Muslim community to which Ali and her family belong.

She has performed the piece in classrooms and dining halls, galleries and streets all over the world. An anomaly, the Buddhist Bug wordlessly interacts with curious onlookers. It prompts an investigation of displacement and belonging, said Ali, and expresses the artist’s own spiritual struggle between Islam and Buddhism.

“To the Bug, they think they’re a perfect fit in whatever situation they’ve come into being,” she said. “But then they notice the people are looking a little strangely at them.”

There’s then a dawning realization of dislocation. “You think you belong, but others start to clue you in that you’re an ‘other.’”

Confrontation and humor

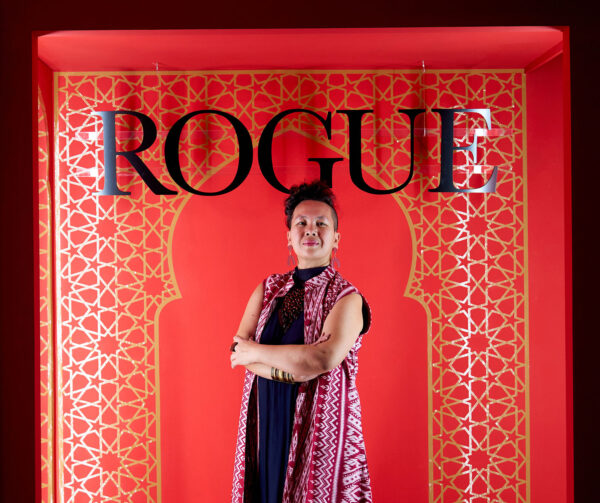

The second work in “Anida Yoeu Ali: Hybrid Skin, Mythical Presence” was The Red Chador, an ongoing series of silent performances that confront fears of the racialized other. “If you encounter The Red Chador,” asks Ali on her website, “will you fear her or walk with her?”

Sparkly and sequined, this garment is both a comment on hypervisibility and a protest against misogyny and anti-Muslim racism. At the same time, Ali weaves a spirit of cheekiness and joy into The Red Chador. It sits at the “intersection of fabulousness and feminism,” she said.

Even though she tackles serious political issues in her practice, Ali animates her work with playfulness and over-the-top humor.

“That’s the other part of our humanity that I think, in these dire times, we don’t lean into enough,” she said. “Sometimes we take ourselves too seriously; we’re a little afraid to laugh or to be ridiculous.”

The in-between

Also crucial to Ali’s practice is her identity as a transnational artist. With one foot in the United States and another in Southeast Asia, she has embraced the in-between place as a point of power. “It’s a powerful idea for provocation — a powerful impetus for it.”

That philosophy informs her teaching practice, too. In her classes, which span filmmaking, writing, movement and performance, she challenges students to share their work in public.

“Art can happen anywhere and everywhere,” Ali said. “Don’t wait for a museum or gallery or white walls to put your work up.”

UW Bothell students also benefit from her international presence. Ali makes a point of taking photos and shooting video of exhibits as she travels. She uses these to introduce students to diverse artists working in other parts of the world — artists who might not have an established presence in the West.

Threads of the Ummah

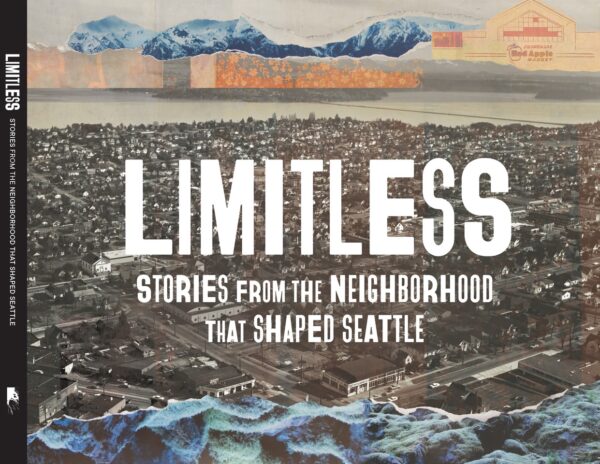

In autumn 2024, Ali taught “Contemporary Muslim Artists,” which culminated in an interactive installation called “Threads of the Ummah.” All 29 students collaborated to create a timeline celebrating Muslim contributions to the world.

It was an emotional experience for some viewers. “People were in tears because they had never seen Muslim culture represented in a positive public light before,” said student Liam Negron.

Negron and classmate Sam Owens, who each received their bachelor’s degree in Culture, Literature & the Arts in June 2025, took multiple classes with Ali. What kept them coming back? “She has a way of pushing you out of your comfort zone,” said Owens. “She’s so passionate about her art, it inspires you to want to do more.”

Negron said he learned to persevere through creative setbacks in Ali’s classes. “She’s very blunt and direct about how I’m going to do better,” he said. “Not that I can or have to, but the potential is there. I’ll do it. I’ll be successful.”

Leaning into the power of Ali’s belief, students imagine — and manifest — new possibilities for themselves and their work.

“Anida’s tremendous accomplishments are a gift to our campus,” said Berger, “most especially in the students who get to take her classes but also to the broader campus community, which benefits from the ways she brings color, performance and the arts to UW Bothell.”

“[Ali] has a way of pushing you out of your comfort zone. She’s so passionate about her art, it inspires you to want to do more.”

Sam Owens, Culture, Literature & the Arts ’25