Jill Freidberg was 15 years old the first time she was arrested for chaining herself to something in an act of civil disobedience. Today, activism continues to drive her work as an educator, an oral historian and an award-winning documentary filmmaker.

Over the years, her lifelong passion for storytelling has evolved to take on new forms — starting with an interest in photography as a child.

“I remember thinking that the problem with photography was that the people that you were taking pictures of didn’t really have a chance to speak for themselves,” said Freidberg, a lecturer in the University of Washington Bothell’s School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences. “That was my motivation for going into documentary filmmaking — it just seemed like a powerful tool for social change.”

Later in her career, Freidberg again felt that the medium of her storytelling didn’t give people enough of an opportunity to speak for themselves. For the past decade, she’s shifted her focus to collecting oral histories, working in partnership with those who share their stories.

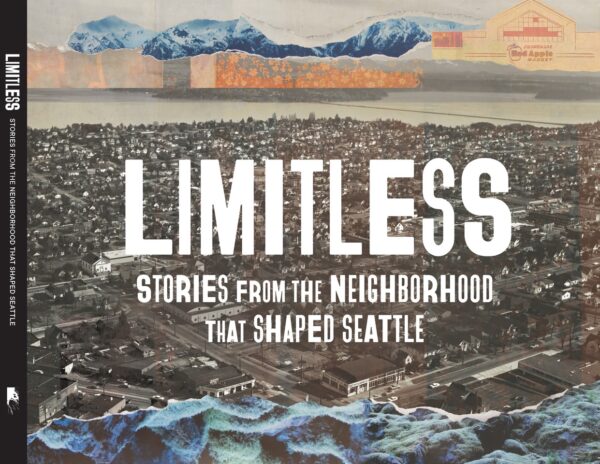

And the thread that binds these histories? Seattle’s Central District — the place she calls home and the subject of her latest work, “Limitless: Stories from the Neighborhood that Shaped Seattle.”

A hyperlocal focus on community

Freidberg has lived most her life in the Pacific Northwest — from Eugene, Oregon, to Vancouver, British Columbia. She first lived in Seattle’s Central District in the mid-90s.

“That was also a motivator for the project, because as a white person I was part of yet another wave of gentrification into the neighborhood,” she said. “So it felt important to use my skills at the neighborhood level to offset that process that I was a part of.”

In the early 2000s, Freidberg had been making documentary films about social movements in southern Mexico when she reached a crossroads, she said. “I was at a point where I felt like either I was going to live in Mexico full time and not have the luxury of leaving when things got really bad, or I was going to stay here in Seattle. I decided to stay put, and that was a conscious decision that whatever creative work I did would be hyperlocal and rooted in the issues that were affecting people in the neighborhood — in this case, displacement and gentrification.”

The Central District is Seattle’s historically redlined neighborhood. From the ’30s to the ’70s, it was the area where people of color, predominantly Black residents, were allowed to own property. Outside of the district, the real estate industry, banks and legislation worked together to keep people of color relegated to one part of the city — an area where many community services and infrastructure were also neglected.

“The outcome of this political and economic reality was that the people who lived there had to overcome these challenges through innovation, creativity, mutual aid, resistance and solidarity,” Freidberg said. “The result was that all those processes actually shaped the whole city.”

The spirit of a grocery store

When developers closed the Red Apple grocery store at 23rd and Jackson Street in 2018, Freidberg was heartbroken.

“It felt like a community center masquerading as a grocery store in a lot of ways,” she said. “I wanted to use my existing skills to do something and felt that recording the stories of the people who worked and shopped there would be a good way to preserve what it was about the place that made it so important to the community.”

She launched the Shelf Life Community Story Project to capture the stories, operating out of an empty storefront next to the Red Apple. Aiding her in the collection of the oral histories were Dominique Meeks and Mayowa Aina, both UW graduates.

“The Central District has always reflected the creativity and resilience of African American communities nationwide, transforming limited resources into joy, culture, opportunity and belonging,” Meeks said. “Through these interviews, you hear generations expressing love, anger, hope, frustration, pride and perseverance — often without the benefit of inherited wealth or a blueprint. It reaffirmed what I’ve always known: African Americans are repositories of innovation and endurance. We are, truly, walking miracles.”

The team collected more than 70 interviews over 18 months. The audio interviews were then developed into a podcast series.

“I wanted to use my existing skills to do something and felt that recording the stories of the people who worked and shopped there would be a good way to preserve what it was about the place that made it so important to the community.”

Jill Freidberg, lecturer, School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences

Stories preserved in ink

The Shelf Life project was supported, in part, by grants from King County 4Culture and the Seattle Office of Arts and Culture. It now sits within the umbrella of Freidberg’s work at Wa Na Wari, a center she co-founded to support Black art and stories in the district.

Some of the oral histories were developed into the podcast, but Freidberg said that not all of them were best suited to an audio medium. She then had the idea to publish a book to feature some of the stories that didn’t make the podcast.

With the grant money, she was also able to work with local artists to create illustrations to go with the stories. She curated the collection to fit within several themes, such as migration, childhood and art. The stories then provided prompts for the artists.

The book was published in November 2025.

“There’s been a really positive response,” Freidberg said. “It feels good to know that the stories are out there working their way through the communities who told them and through people who know nothing about the neighborhood but now maybe do because of this book.”

“When we got off the plane at SeaTac, we got a cab and my mother told the driver that she wanted to be in the Asian part of town. So the first place he took us was the Bush Hotel. My mother is in her tweed suit with her alligator purse, alligator pumps, and gloves, and she’s walking to the door, and she sees all those men hanging around, so she comes back and tells him, “This—no good,” So he pulled up to another hotel. It was very clean but old. The sign on the hotel said “NP Hotel” and we stayed there. I was twelve. I thought NP stood for “Negro People!” —Words by Annie Harper, art by Chi Moscou-Jackson.

Impacts in the community

Freidberg believes the book will increase awareness about the history, struggles and resilience of Seattle’s Central District. Even more than awareness, she wants it to create change.

“Stories have the power to shift people’s behaviors,” she said. “For readers who may be moving into a neighborhood like the Central District — who are more affluent and more likely to be white — these stories will make them better neighbors by giving them an understanding of the historical context that they’re moving into, the impact their being there has and the ways they can either exacerbate or mitigate that.”

For both the interviewers and the subjects, the project has already had an impact through the community building and connections it provides.

“What I enjoyed most was hearing people’s stories, laughing with them, learning with them and crying with them,” Aina said. “I was inspired, frustrated, intrigued and empowered. Putting all the stories together and creating something new with Jill and Domonique was so much fun — and it’s just been incredible to see how it was grown and evolved over the years and how many people it has touched.

“This work reinforces my belief that storytelling is how we change the world.”