The term “food desert” was first used in the 1990s to refer to areas where people lacked access to affordable, healthy food options. The phrase was later found by some scholars to lack a critical component to the food equity problem.

“The term ‘food desert’ naturalizes the process. In relation to physical geography, ‘desert’ makes it sound like it’s a natural state,” said Natalie Vaughan-Wynn, a doctoral candidate in the University of Washington’s Department of Geography. “But we know that these areas exist because of human choices, processes and priorities. There’s nothing natural about them.”

In 2018, Karen Washington, a food justice activist, coined a new term to reflect the intersectional issues around food equity: food apartheid.

“The origin of the word apartheid means separation, but that separation happens through an existing systematic structure and relates to the racial capitalism perspective,” said Dr. Jin-Kyu Jung, a professor in UW Bothell’s School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences.

In their recently published paper, “Digital food apartheid: The uneven food geographies of Seattle in the era of Amazon,” Jung and Vaughan-Wynn found that these lines of separation are not just physical but also digital.

Spatial equity

When it comes to food access, Jung said, spatial equity is more complicated than simply looking at points on a map.

“It’s not just about the physical distance. It’s also relative,” he said, adding that two people could live the same distance from a grocery store, yet have different levels of access. “Time is a critical factor — such as time to travel by car versus time to travel by public transit or to walk.

“These factors of spatial equity also relate to other aspects we often see in issues of social inequity.”

Health can create barriers to access, as some may be unable to travel to a grocery store, instead relying on delivery or other support. Until the COVID-19 pandemic, however, delivery wasn’t an affordable option for those receiving Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits, commonly referred to as SNAP or “food stamps.”

Vaughan-Wynn, who is a Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux descendant, said these kinds of questions around food policy, food justice and food sovereignty lie at the center of her work and scholarship.

“Being part of a family who relied on food assistance, I’ve always had an intergenerational and intimate commitment to these issues,” she said, noting that when Jung guest lectured in one of her courses, she became interested in his spatial thinking around food access. The pair then connected on their shared passions and began thinking about a project to further explore these issues.

Solving the problem of food apartheid, Vaughan-Wynn said, isn’t as simple as building a grocery store where one is lacking. Rather, it requires a look into a deeper questions, such as: “Why wasn’t there a grocery store in the first place?” and “If not a grocery store, where are people getting food?”

When it comes to food access, spatial equity is more complicated than simply looking at points on a map. Time is a critical factor — such as time to travel by car versus time to travel by public transit or to walk.

Dr. Jin-Kyu Jung, professor, School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences

Food assistance

In 2020, the U.S. Department of Agriculture fast-tracked the SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot as a means for those receiving benefits to have access to food while social distancing during the national health crisis. The program itself, however, was approved long before the pandemic.

The pilot program was initially intended to be tested among a few pilot retailers in only a few states in 2019 and 2020 after it was authorized in the 2014 Farm Bill. When the greater need arose during the pandemic, it was quickly rolled out and became available in 45 states by the end of September 2020.

As Jung and Vaughan-Wynn discovered in their research, the success of this new program as a tool for providing greater spatial equity largely depended on the retailers approved for its use.

As they looked to narrow the scope of their research, the pair decided to focus on the greater Seattle metropolitan area. Because approved vendors needed to already have the digital infrastructure in place to handle online grocery shopping, larger companies made up the bulk of eligible retailers.

Amazon Fresh was among the first to be approved by the USDA for the online purchasing program. Headquartered in Seattle, Amazon seemed the perfect place to start.

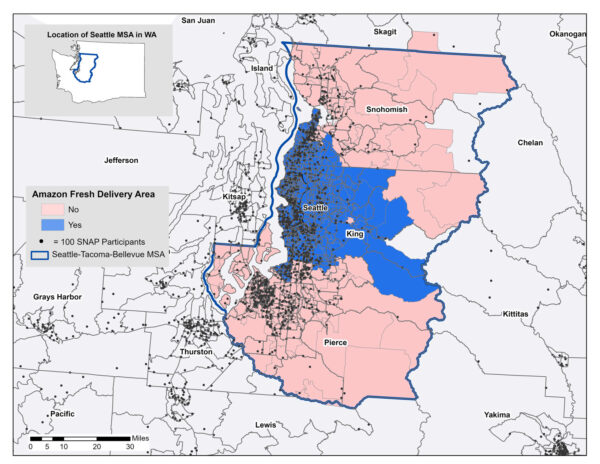

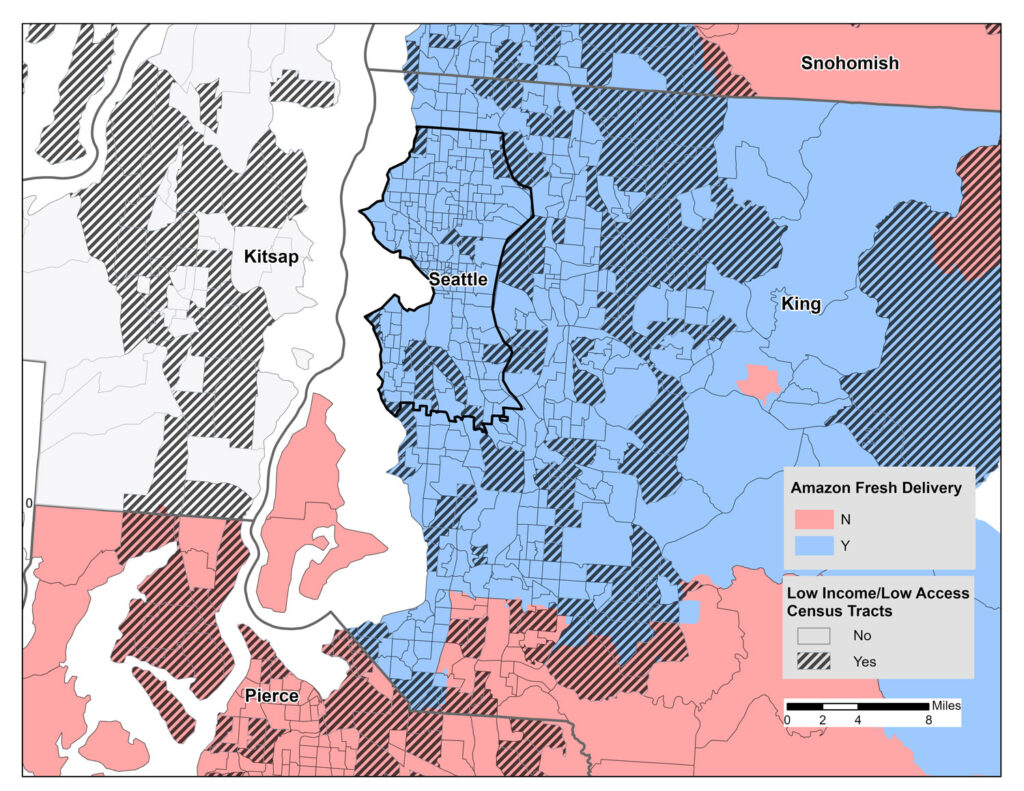

Jung and Vaughan-Wynn began by searching each zip code — 172 in total — through the Amazon Fresh website and creating a geographic information system map of the data. They then overlaid data on the SNAP participants and USDA low-income designations to visualize the program’s operationalization.

Retail giant

The researchers were curious to see whether there was any correlation with historically redlined areas — areas where residents were deprived of resources and opportunities based on race. What they found was that a new kind of redlining might be emerging: a technological redlining.

In their paper, Jung and Vaughan-Wynn wrote: “We argue that the simple reality that Amazon determines which foods can be delivered to which areas is a form of technological redlining. In the specific context of food, this can be understood as food apartheid by the digital.”

Even for those who lived in delivery areas, the team found there may be differences in the digital shopping experience based on the payment method. When using the search function to filter for benefits-eligible products, they discovered that junk foods such as candy, cookies and crackers were often the top results.

“Algorithm-generated advertisements and search results can be tied to a payment method, in this case an EBT card,” Vaughan-Wynn said. “We know that other choices markets make are based on race and income, and this might be another area where that is the case.”

Change opportunity

The outcome of these digital tools, Vaughan-Wynn added, lies in how they’re used. “Human behavior can be positively impacted by digital interventions and algorithms,” she said.

The same tools that might currently be pushing low-income consumers to make unhealthy choices, for example, could instead be used to promote healthy ones.

While the research pointed to ways the digital landscape may be exacerbating the issue of food apartheid, Jung said no singular map can tell the full story. The process is iterative, and more investigation is needed.

The team hopes to expand their research to look at other areas and to center the perspectives of those impacted by interviewing SNAP recipients.

“This type of research could be not only about revealing these issues but also about looking at what would be the ways to speak back to this,” Jung said.

“And as we interpret the outcomes of this research, we want to flip the script and not only look at the deficits of these areas but also their resilience.”