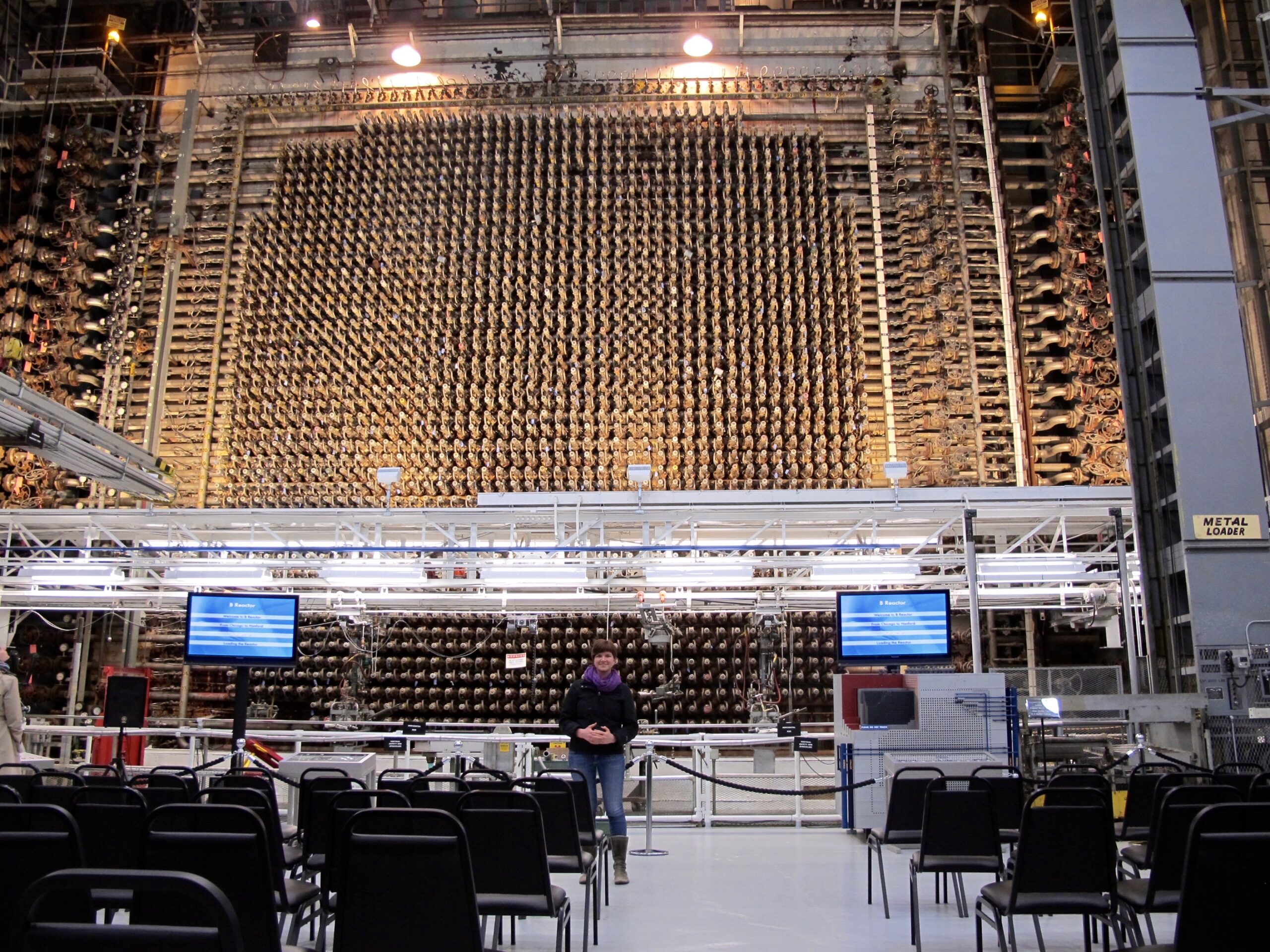

The first time Dr. Shannon Cram stood inside the B Reactor at the Hanford Nuclear Site, she cried

“It’s this really impactful space. I surprised myself. I’m not a public crier, but I walked into the middle of the reactor, and it felt as if my feet were grounded in cement as I looked at its face,” said Cram, associate professor in the University of Washington Bothell’s School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences. “I cried just thinking about the scale of this place, the lives and landscapes it has changed.”

Located in Eastern Washington’s Tri-Cities area, Hanford was used to produce plutonium as part of the atomic weapons program known as the Manhattan Project. The site remained active for more than 40 years — from World War II through the Cold War. Now a Superfund site spanning more than 500 square miles, the environmental cleanup for the site is the largest in U.S. history and continues to this day.

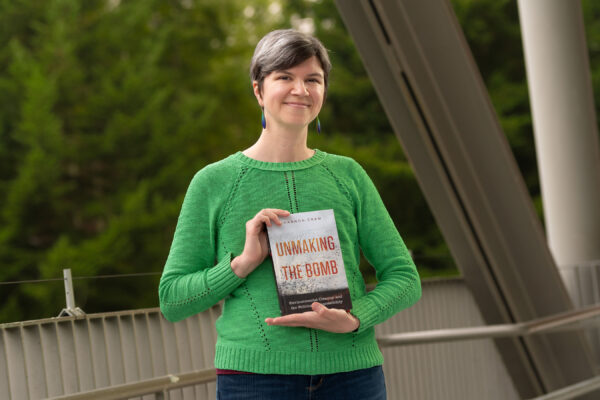

Just a year before her visit in 2005, Cram had never even heard of Hanford. After, the nuclear site would become not only the topic of her master’s thesis and doctoral dissertation but also her research obsession for the next 20 years — a project culminating in her recently published book, “Unmaking the Bomb: Environmental Cleanup and the Politics of Impossibility.”

A lasting impact

Cram was born in Seattle and grew up in California. She completed her undergraduate studies at Cal Poly Humboldt, receiving a bachelor’s degree in Geography with a minor in Women’s Studies. She then spent a summer living with a friend in Seattle before heading off to graduate school.

While looking for summer work, she saw a flyer about a job canvassing for the advocacy nonprofit WashPIRG (Washington Public Interest Group) in support of Initiative 297. If enacted, I-297 would prevent out-of-state waste from being brought to Hanford and would impose new requirements on the handling of the site’s current waste. Cram became a campaign field manager and spent summer 2004 going door to door across the state talking to people about Hanford.

While completing her master’s degree in Geography at the University of Oregon, she then signed up for a tour of Hanford’s B Reactor. After that visit in 2005, she found she couldn’t stop thinking about Hanford.

“It stayed with me,” she said.

It also inspired her to change her master’s thesis topic from ecotourism in Costa Rica to a study of Hanford. She continued probing into the site while working on her doctorate in Geography, with an emphasis in Science and Technology Studies, at the University of California, Berkeley.

Even once she began teaching her own courses at the University of Washington Bothell in 2015, Hanford remained at the center of her research.

A quest to present complexity

As a young woman in the early stages of her research, Cram was filled with a fire to enact change. She recalls passionately taking to the podium at a public meeting to demand that Hanford be cleaned up immediately — without further delay.

Her line of inquiry took her on a long journey, both in and on the periphery of Hanford. She interviewed more than 100 people. She joined Department of Health staff members as they collected samples by boat. For a decade, she contributed to policy recommendations as a member of the Hanford Advisory Board. She even traced a “phantom limb” — a polyurethane limb that encased radioactive bones used for experimental purposes — back to a deceased worker who happened to be the father of her former landlord in California.

Yet, after two decades spent examining the site and expanding her understanding of nuclear waste and environmental policy, Cram came to the same conclusion that she faces and presents to readers in her book: Hanford will likely never be clean, not in the true sense of the word.

“Our definition of clean doesn’t mean uncontaminated. It means that there’s an ‘acceptable risk’ of cancer,” she said. “Many of our environmental policies in the U.S. follow that logic, making the policies themselves toxic by their very nature.”

But while Cram had come to reckon with the reality that cleanup was not what she had initially understood it to be, she still yearned to provide people with a more complex picture of Hanford.

“What I want the general public reading this book to understand is that clean does not mean the waste goes away. Clean means managing and being in relation with waste forever,” she said. “And thus, how can we think about being in relation with that waste in a more equitable sense?”

What I want the general public reading this book to take away from it is that clean does not mean the waste goes away. Clean means managing and being in relation with waste forever. And thus, how can we think about being in relation with that waste in a more equitable sense?

Dr. Shannon Cram, assistant professor in the School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences

Reckoning with the past

Cram’s mother grew up in an agricultural community near Hanford where there was environmental sampling during the years of production at the nuclear site. Although she didn’t know it at the time she started her research, Cram’s grandfather had worked a contract job building roads at Hanford during the Cold War.

“He told me he’d never work a job there again because afterward Hanford held his equipment for decontamination. It not only meant that he had to rent equipment for his next job, which was a hassle, but later when he thought about it, it dawned on him that he and his team were also exposed and covered in dust,” she said. “It made him concerned for their health.”

Her grandfather also built runways in the Northern Mariana Islands during World War II and remembers watching the Enola Gay (the plane which was carrying the atom bomb) take off on Aug. 6, 1945, and head for Hiroshima, Japan.

For Cram, uncovering her own family’s ties to Hanford added complexity to how she viewed the site. “Part of my reckoning with Hanford and what it produced has also been recognizing my ancestral ties to settler colonialism, the violence that came with settling this area, and thus, the ways that my family helped make Hanford and the bomb possible,” she said.

Over the course of her research, Cram was also forced to reckon with toxicity at another level as one by one, everyone in her family was diagnosed with cancer, including her. Her father was diagnosed with colon cancer, and then her mother with breast cancer. Cram received her own test results confirming breast cancer just a few weeks after her mother’s funeral. Her sister was later diagnosed as well.

Living and learning with toxicity

While working toward her graduate degrees, Cram read books on toxicology, environmental policy and the history of nuclear fallout between chemotherapy appointments. In the margins of her research notebooks and class notes for school, she scribbled down her latest lab results and blood cell counts.

In the 20 years that Cram spent studying Hanford, her journey to completing a book on the subject was interwoven with her own experience with contamination and toxicity.

“My book is about Hanford, but it’s much more about how we reckon with a contaminated world, how we think about living and dying with toxicity and how we’ve structured our environmental policy, clean up and restoration in a way that tries to achieve ‘reasonable harm,’” she said.

A common theme in her book and in her own life is uncertainty — the uncertainty that comes with cancer and contamination. As she writes:

“It matters that I want to know what caused my family’s cancer. And it matters that I will never fully be able to answer that question. For although most environmental quality standards are based on statistical models of carcinogenic hazard, it is nearly impossible to identify when an individual instance of cancer results from daily life in a contaminated environment.”

Cram said that in the face of uncertainty, “I want us to think about caring for people who have cancer, workers who have cancer, without making them prove that their illnesses were caused by Hanford. What if we just cared for them, regardless of where it came from?”

The closing of one chapter

With the publication of her book, Cram said this area of research has come to a close, although Hanford will always be a part of her life and work. She plans to continue bringing Hanford and related themes into her classrooms. She often asks her students to raise their hands if they’ve heard of Hanford. On average, only two people in a class of 50 do.

“I will always care about Hanford, and I’ll always be tracking the cleanup and the politics of it,” she said. “Though I’m done with this particular book, I will continue to write about toxicity and cancer and everyday life outside the context of Hanford. I will be exploring these same themes in different spaces.”

Cram is also already planning her next book, which will center around the concept of previvor-ship — the surviving of a predisposition to certain diseases, such as cancer — and will explore the gendered landscape of inequitable survivorship.

Join Dr. Shannon Cram at the book launch of “Unmaking the Bomb: Environmental Cleanup and the Politics of Impossibility,” at the University Book Store on Nov. 2 at 6 p.m. The event is free to attend, though registration is required. Visit the University Book Store website to learn more and to register.