By Douglas Esser

Marc Studer photos

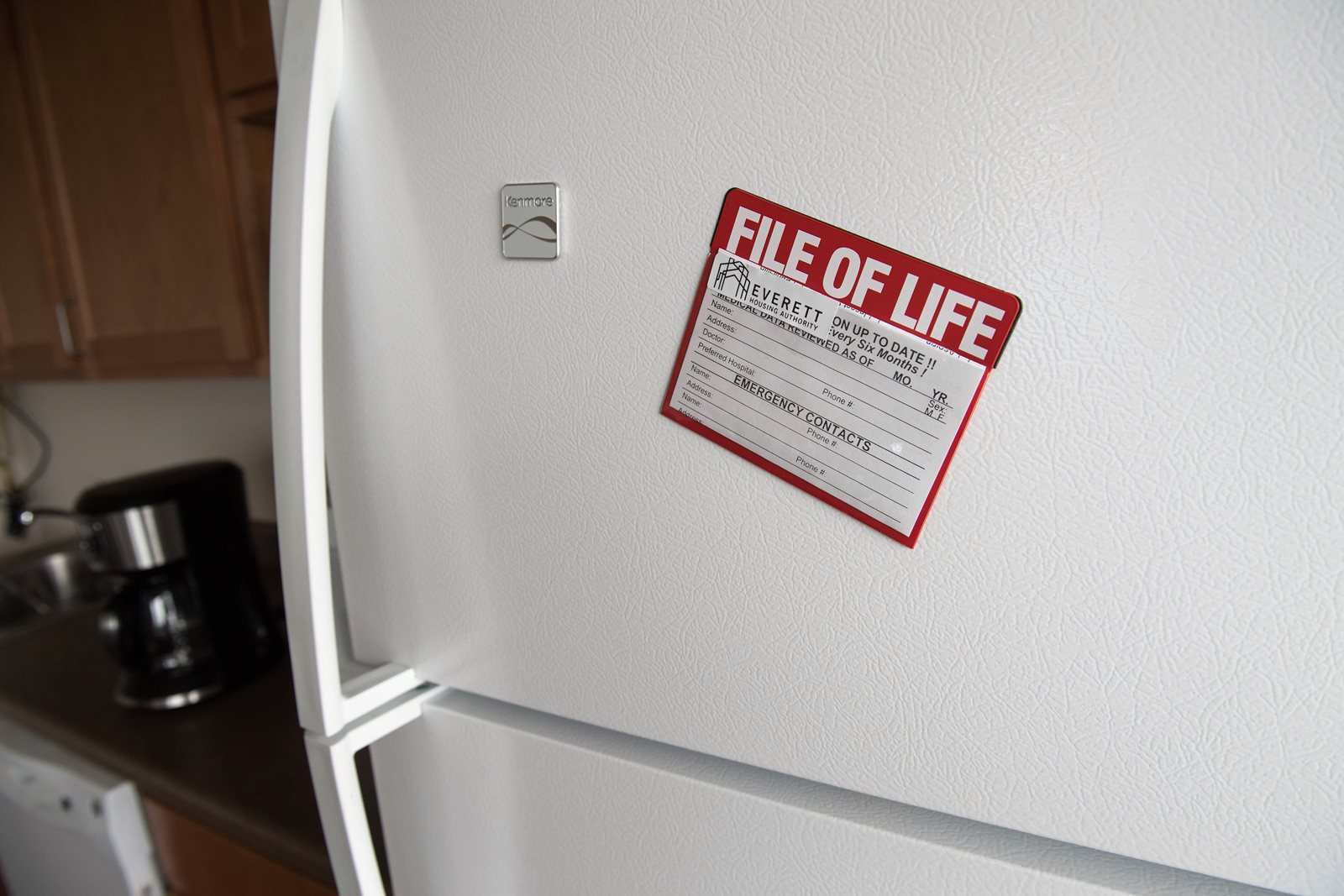

What’s on your refrigerator door? The fridge in many homes is a magnet for art, cartoons, clippings and magnets. The often-opened door is the perfect place for reminders and notes. It could also save a life.

Here’s how. For their community health practice, University of Washington Bothell RN to BSN students are helping some vulnerable residents in Everett Housing Authority (EHA) apartments put together a “File of Life.”

Everyone should compile such information, but some elderly, the disabled or mentally ill could use a little help completing the form.

“I love going into people’s apartments and seeing it on the fridge,” she said.

The forms are published by the nonprofit File of Life organization, based in West Suffield, Connecticut. The most popular version comes with a red plastic holder and a refrigerator magnet. Since last year, UW Bothell RN to BSN students like Risa Fukuda, left, have been helping stick that vital information on housing residents’ refrigerators as part of their field work in the course, Population-Based Health in Community Practice.

There’s educational value in working with community members in their own homes and understanding how they live, said Annie Bruck, senior lecturer and faculty coordinator for the UW Bothell community health nursing course. It changes the power differential.

“As a nurse, you’re not necessarily in your comfort zone. You’re not in your hospital. You’re not in your clinic. You are not with doctors and nurses,” Bruck said. “Working with community members in their homes, you’re there, one-on-one with clients and asking them questions in their setting, in their world, and that makes a difference. You get to see the capabilities and challenges folks have in a very different way than in a hospital or clinic.”

Bruck’s students Risa Fukuda and Hannah Mhyre, along with Ishwerjot Kaur, Rouella Rillo and Aster Tesfaye — three students of UW Bothell lecturer David Baure — met in April with EHA’s Emelander and Kaikai at the Bakerview Apartments for a spring quarter orientation.

Bakerview has 151 subsidized units and Broadway Plaza 190. They serve seniors and adults with disabilities. Many residents are formerly homeless, surviving on their Social Security or disability payments. Stabilizing the population with services tied to the housing saves taxpayers money, Kaikai said.

Because of age and disabilities, the EHA residents are more likely than average to call 911, and arriving fire department paramedics now know to look on refrigerators for the emergency information, Kaikai said.

“It’s actually working,” he said. “It saves lives.”

Two former students who started File of Life work at the Bakerview Apartments in 2017, Caerissa Fawkes and Hannah Persyn, detailed some of the challenges that came with this field work in their final report and poster.

They found that about 20 percent of the residents did not speak English, so Fawkes and Persyn used the translation feature on their phones plus help from multilingual friends to create Russian, Vietnamese and Spanish versions of the File of Life. Another barrier was the number of residents with mental disabilities or disorganization. Other residents were unavailable or hard to contact or simply refused to take the cards. In the end, the students reached about 60 percent of the residents.

At the orientation meeting this year, Kaikai and Emelander advised students to kick off their File of Life campaign with a lobby event with snacks and flyers. An Americorps worker familiar to the residents, Spencer London, goes door-to-door with the students to introduce them and help everyone feel comfortable.

Filling out a File of Life card or updating a card’s information takes about 30 minutes. The nursing students gather as much information as possible for the card, respecting the privacy of medical records and not intruding unwelcome into apartments.

A File of Life visit also is a social experience for the residents, some of whom seldom leave their apartment. Kaikai urged students to engage with the residents. “Talk to people if you have a chance, and once some of them get started, they’ll tell you what’s going on, how they ended up here and what’s in their past,” said Kaikai, left.

Some residents are more likely to talk with the students than the building coordinator, Emelander said. Making a note about a diabetes medication for example, can lead to a helpful discussion about diet. “Residents like opening up to students — talking about medical history — versus talking to someone in the resident services position,” she said.

This kind of community engagement is both helpful for residents and inspiring for students, said Fawkes (BSN August ’17). “It really changed the way I viewed nursing and the ways in which I was capable of helping in my community,” said Fawkes, who now works as a school nurse in Redmond, Washington.

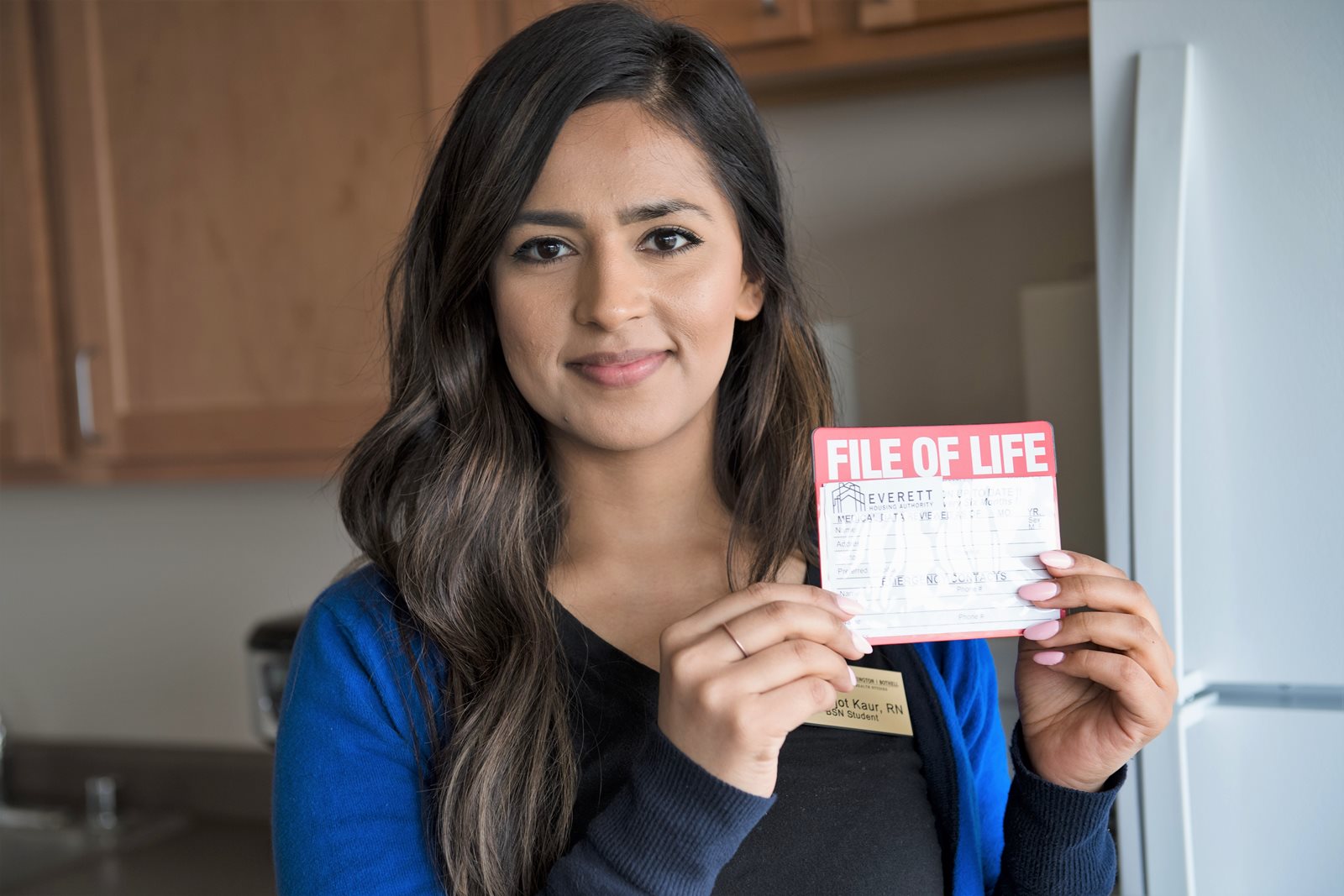

Kaur, a current BSN student who works at Good Samaritan Hospital in Puyallup, Washington, also appreciates the value of the File of Life project.

“I really like the idea of putting this on the refrigerator. It’s easy and accessible,” said Kaur, who planned to share the idea at her hospital. “It’s good to know what’s missing in our community and what we can do to make the community better.”

Her instructor, Baure, left, said the community health assignment helps students think on a larger scale and take the lead in the field.

“They’re really leading the changes they’re going to see in their communities,” he said. “This is one of several projects where students take the initiative to create systemic change beyond typical clinic settings.”

Students in the course finish 52 hours of field work in the quarter. They also complete weekly online reports and discussions. They wrap up with a poster session on campus and a report to the community partner.

UW Bothell is fortunate to have the support of the Everett Housing Authority and its staff, Bruck said. “They are educators of our students in a way we on campus can’t do.”

Another lesson for students is the value of working together to promote health, Bruck said. “It takes partnerships.”